Modelica.Mechanics.MultiBody.UsersGuide.Tutorial.LoopStructures

Modelica.Mechanics.MultiBody.UsersGuide.Tutorial.LoopStructures

Modelica.Mechanics.MultiBody.UsersGuide.Tutorial.LoopStructures

Modelica.Mechanics.MultiBody.UsersGuide.Tutorial.LoopStructuresThe MultiBody library has the feature that all components can be connected together in a nearly arbitrary fashion. Therefore, kinematic loop structures pose in principal no problems. In this section several examples are given, the special treatment of planar loops is discussed and it is explained how a kinematic loop structure can be modeled such that the occuring non-linear algebraic equation systems are solved analytically. There are the following sub-chapters:

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Introduction | |

| Planar loops | |

| Analytic loop handling |

Modelica.Mechanics.MultiBody.UsersGuide.Tutorial.LoopStructures.Introduction

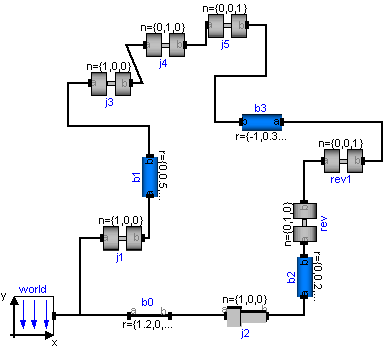

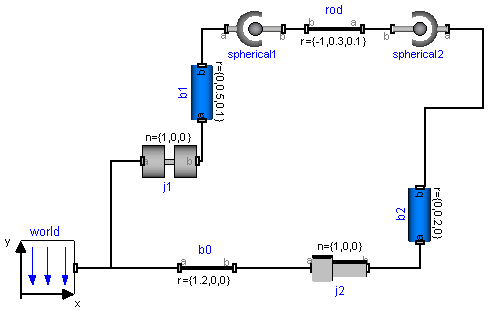

Modelica.Mechanics.MultiBody.UsersGuide.Tutorial.LoopStructures.IntroductionIn principal, now special action is needed, if loop structures occur (contrary to the ModelicaAdditions.MultiBody library). An example is presented in the figure below. It is available as MultiBody.Examples.Loops.Fourbar1

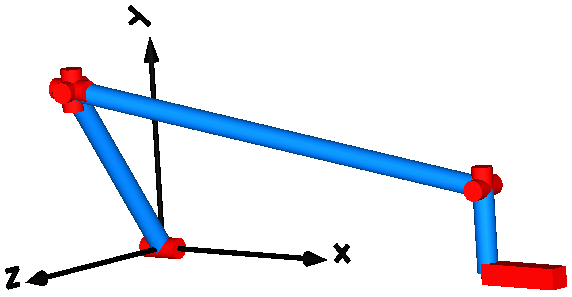

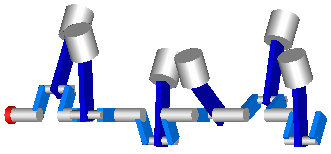

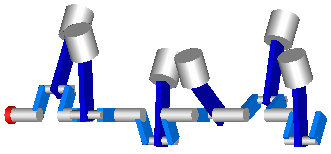

This mechanism consists of 6 revolute joints, 1 prismatic joint and forms a kinematical loop. It has has one degree of freedom. In the next figure the default animation is shown. Note, that the axes of the revolute joints are represented by the red cylinders and that the axis of the prismatic joint is represented by the red box on the lower right side.

Whenever loop structures occur, non-linear algebraic equations are present on "position level". It is then usually not possible by structural analysis to select states during translation (which is possible for non-loop structures). In the example above, Dymola detects a non-linear algebraic loop of 57 equations and reduces this to a system of 7 coupled algebraic equations. Note, that this is performed without using any "cut-joints" as it is usually done in multi-body programs, but by just appropriate symbolic equation manipulation. Via the dynamic dummy derivative method the generalized coordinates on position and velocity level from one of the 7 joints are dynamically selected as states during simulation. Whenever, these two states are no longer appropriate, states from one of the other joints are selected during simulation.

The efficiency of loop structures can usually be enhanced, if states are statically fixed at translation time. For this mechanism, the generalized coordinates of joint j1 (i.e., the rotation angle of the revolute joint and its derivative) can always be used as states. This can be stated by setting parameter "enforceStates = true" in the "Advanced" menu of the desired joint. This flag sets the attribute stateSelect of the generalized coordinates of the coresponding joint to "StateSelect.always". When setting this flag to true for joint j1 in the four bar mechanism, Dymola detects a non-linear algebraic loop of 40 equations and reduces this to a system of 5 coupled non-linear algebraic equations.

In many mechanisms it is possible to solve the non-linear algebraic equations analytically. For a certain class of systems this can be performed also with the MultiBody library. This technique is described in section "Analytic loop handling".

Modelica.Mechanics.MultiBody.UsersGuide.Tutorial.LoopStructures.PlanarLoops

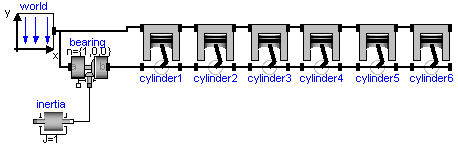

Modelica.Mechanics.MultiBody.UsersGuide.Tutorial.LoopStructures.PlanarLoopsIn the figure below, the model of a V6 engine is shown that has a simple combustion model. It is available as MultiBody.Examples.Loops.EngineV6.

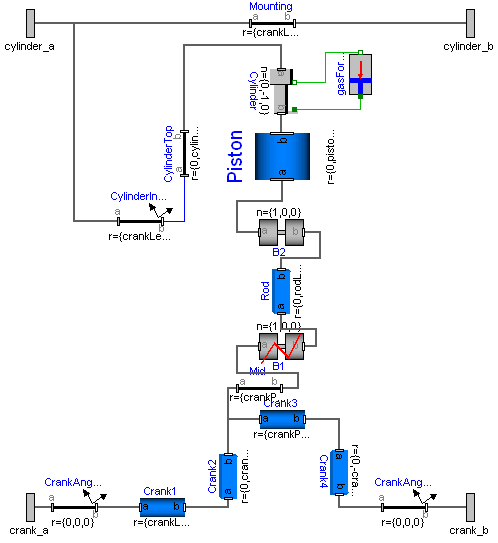

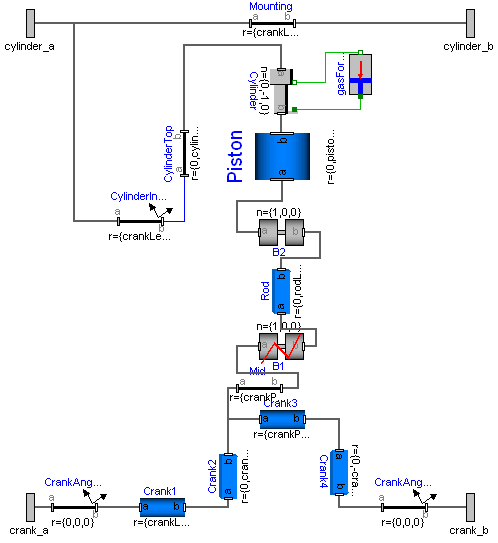

The Modelica schematic of one cylinder is given in the figure below. Connecting 6 instances of this cylinder appropriately together results in the engine schematic displayed above.

In the next figure the animation of the engine is shown. Every cylinder consists essentially of 1 prismatic and 2 revolute joints that form a planar loop, since the axes of the two revolute joints are parallel to each other and the axis of the prismatic joint is orthogonal to the revolute joint axes. All 6 cylinders together form a coupled set of 6 loops that have together 1 degree of freedom.

All planar loops, and especially the engine, result in a DAE (= Differential-Algebraic Equation system) that does not have a unique solution. The reason is that, e.g., the cut forces in direction of the axes of the revolute joints cannot be uniquely computed. Any value fulfills the DAE equations. This is a structural property that is determined by the symbolic algorithms. Since they detect that the DAE is structurally singular, a further processing is not possible. Without additional information it is also impossible that the symbolic algorithms could be enhanced because if the axes of rotations of the revolute joints are only slightly changed such that they are no longer parallel to each other, the planar loop can no longer move and has 0 degrees of freedom. Algorithms based on pure structural information cannot distinguish these two cases.

The usual remedy is to remove superfluous constraints, e.g., along the axis of rotation of one revolute joint. Since this is not easy for an inexperienced modeler, the special joint: RevolutePlanarLoopConstraint is provided that removes these constraints. Exactly one revolute joint in a every planar loop must be replaced by this joint type. In the engine example, this special joinst is used for the revolute joint B2 in the cylinder model above. The icon of the joint is slightly different to other revolute joints to visualize this case.

If a modeler is not aware of the problems with planar loops and models them without special consideration, a Modelica translator, such as Dymola, displays an error message and points out that a planar loop may be the reason and suggests to use the RevolutePlanarLoopConstraint joint. This error message is due to an annotation in the Frame connector.

connector Frame

...

flow SI.Force f[3] annotation(unassignedMessage="..");

end Frame;

If no assignment can be found for some forces in a connector, the "unassignedMessage" is displayed. In most cases the reason for this is a planar loop or two joints that constrain the same motion. Both cases are discussed in the error message.

Note, that the non-linear algebraic equations occurring in planar loops can be solved analytically in most cases and therefore it is highly recommended to use the techniques discussed in section "Analytic loop handling" for such systems.

Modelica.Mechanics.MultiBody.UsersGuide.Tutorial.LoopStructures.AnalyticLoopHandling

Modelica.Mechanics.MultiBody.UsersGuide.Tutorial.LoopStructures.AnalyticLoopHandlingIn a series of papers and dissertations Prof. Hiller and his group in Duisburg, Germany, have developed systematic methods to handle mechanical loops analytically. The "characteristic pair of joints" method basically cuts a loop at two joints and uses geometric invariants to reduce the number of algebraic equations, often down to one equation that can be solved analytically. Also several multi-body codes have been developed that are based on this method, e.g., MOBILE. Besides the very desired feature to solve non-linear algebraic equations analytically, i.e., efficiently and in a robust way, there are several drawbacks: It is difficult to apply this method automatically. Even if this would be possible in a good way, there is always the problem that it cannot be guaranteed that the statically selected states lead to no singularity during simulation. Therefore, the "characteristic pair of joints" method is usually manually applied which requires know-how and experience.

In the MultiBody library the "characteristic pair of joints" method is supported in a restricted form such that it can be applied also by non-specialists. The idea is to provide aggregations of joints in package MultiBody.Joints.Assemblies. as one object that either have 6 degrees of freedom or 3 degrees of freedom (for usage in planar loops).

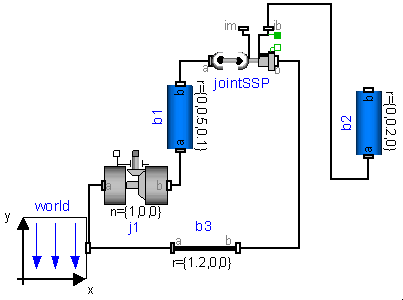

As an example, a variant of the four bar mechanism is given in the figure below.

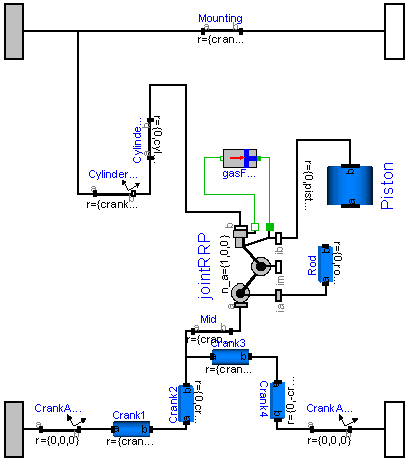

Here, the mechanism is modeled with one revolute joint, two spherical joints and one prismatic joint. In the figure below, the two spherical joints and the prismatic joint are collected together in an assembly object called "jointSSP" from MultiBody.Joints.Assemblies.JointSSP.

The JointSSP joint aggregation has a frame at the left side of the left spherical joint (frame_a) and a frame at the right side of the prismatic joint (frame_b). JointSSP, as all other objects from the Joints.Assemblies package, has the property, that the generalized coordinates, and all other frames defined in the assembly, can be calculated given the movement of frame_a and of frame_b. This is performed by analytically solving non-linear systems of equations (details are given in section xxx). From a structural point of view, the equations in an assembly object are written in the form

q = f1(ra, Ra, rb, Rb)

where ra, Ra, rb, Rb are the variables defining the position and orientation of the frame_a and frame_b connector, q are the generalized positional coordinates inside the assembly, e.g., the angle of a revolute joint. Given angle j of revolute joint j1 from the four bar mechanism, frame_a and frame_b of the assembly object can be computed by a forward recursion

(ra, Ra, rb, Rb) = f(j)

Since this is a structural property, the symbolic algorithms can automatically select j and its derivative as states and then all positional variables can be computed in a forwards sequence. It is now understandable that a Modelica translator, such as Dymola, can transform the equations of the four bar mechanism to a recursive sequence of statements that has no non-linear algebraic loops anymore(remember, the previous "straightforward" solution with 6 revolute joints and 1 prismatic joint has a nonlinear system of equations of order 5).

The aggregated joint objects consist of a combination of either a revolute or prismatic joint and of a rod that has either two spherical joints at its two ends or a spherical and a universal joint, respectively. For all combinations, analytic solutions can be determined. For planar loops, combinations of 1, 2 or 3 revolute joints with parallel axes and of 2 or 1 prismatic joint with axes that are orthogonal to the revolute joints can be treated analytically. The currently supported combinations are listed in the table below. The missing combinations (such as JointSUP or Joint RPP) will be added in one of the next releases.

| 3-dimensional Loops: | |

| JointSSR | Spherical - Spherical - Revolute |

| JointSSP | Spherical - Spherical - Prismatic |

| JointUSR | Universal - Spherical - Revolute |

| JointUSP | Universal - Spherical - Prismatic |

| JointUPS | Universal - Prismatic - Spherical |

| Planar Loops: | |

| JointRRR | Revolute - Revolute - Revolute |

| JointRRP | Revolute - Revolute - Prismatic |

On first view this seems to be quite restrictive. However, mechanical devices are usually built up with rods connected by spherical joints on each end, and additionally with revolute and prismatic joints. Therefore, the combinations of the above table occur frequently. The universal joint is usually not present in actual devices but is used (a) if two JointXXX components can be connected such that a revolute and a universal joint together form a spherical joint and (b) if the orientation of the connecting rod between two spherical joints is needed, e.g., since a body shall be attached. In this case one of the spherical joints might be replaced by a universal joint. This approximation is fine as long as the mass and inertia of the rod is not significant.

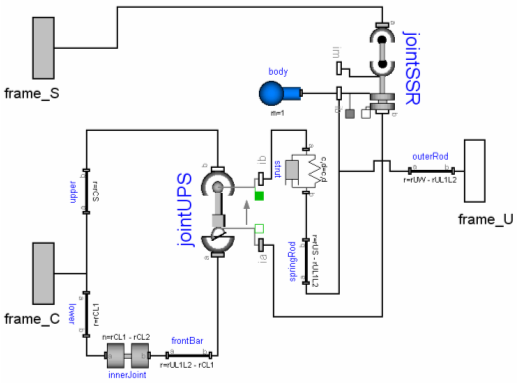

Let us discuss item (a) in more detail: The MacPherson suspension in the next figure is from the Modelica VehicleDynamics library.

The movement of the chassis, frame_C, is computed somewhere else. When the generalized coordinates of revolute joint "innerJoint" (lower left part in figure) are used as states, then frame_a and frame_b of the jointUPS joint can be calculated. After the non-linear loop with jointUPS is (analytically) solved, all frames on this assembly are known, especially, the one connected to frame_b of the jointSSR assembly. Since frame_b of jointSSR is connected to frame_S which is computed from the steering mechanism, again the two required frame movements of the jointSSR assembly are calculated, meaning in turn that also all other frames on the jointSSR assembly can be computed, especially, the one connected to frame_U that drives the wheel. From this analysis it is clear that a tool is able to solve these coupled loops analytically.

Another example is the model of the V6 engine, see next figure for an animation view and the original definition of one cylinder with elementary joints.

It is sufficient to rewrite the basic cylinder model by replacing the joints with a JointRRP object that has two revolute and one prismatic joint, see next figure.

Since 6 cylinders are connected together, 6 coupled loops with 6 JointRRP objects are present. This model is available as MultiBody.Examples.Loops.EngineV6_analytic.

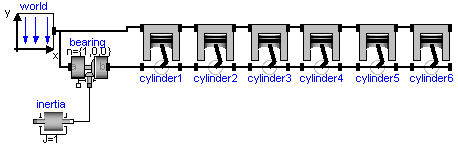

The composition diagram of the connected 6 cylinders is shown in the next figure

It can be seen that the revolute joint of the crank shaft (joint "bearing" in left part of figure) might be selected as degree of freedom. Then the 4 connector frames of all cylinders can be computed. As a result the computations of the cylinders are decoupled from each other. Within one cylinder the position of frame_a and frame_b of the jointRRP assembly can be computed and therefore the generalized coordinates of the two revolute and the prismatic joint in the jointRRP object can be determined. From this analysis it is not surprising that a Modelica translator, such as Dymola, is able to transform the DAE equations into a sequential evaluation without any non-linear loop. Compare this nice result with the model using only elementary joints that leads to a DAE with 6 algebraic loops and 5 non-linear equations per loop. Additionally, a linear system of equations of order 43 is present. The simulation time is about 5 times faster with the analytic loop handling.